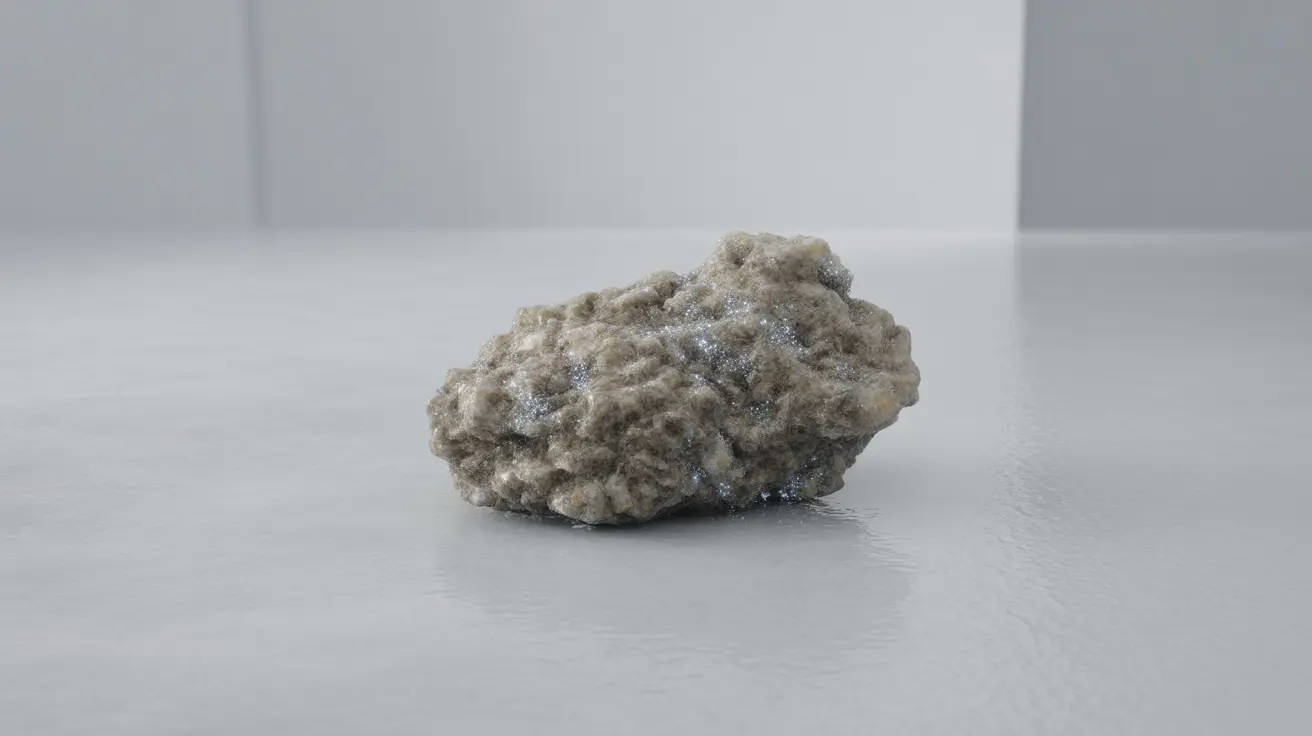

A calcified granuloma represents the body's natural healing response to chronic inflammation, appearing as a small, hardened nodule that has accumulated calcium deposits over time. These formations typically develop when the immune system creates a protective barrier around foreign substances, infections, or irritants that cannot be easily eliminated from the body.

While discovering a calcified granuloma on medical imaging can initially cause concern, these structures are generally benign and often indicate that your body has successfully contained and neutralized a previous threat. Understanding what these formations mean, when they require attention, and how they differ from other conditions can help alleviate anxiety and guide appropriate medical care.

What Are Calcified Granulomas and Their Underlying Causes

Calcified granulomas form through a multi-step process that begins with the immune system's response to persistent irritation or infection. When immune cells encounter substances they cannot effectively remove, they cluster together to form a granuloma - essentially a microscopic wall designed to isolate the problematic material.

Over months or years, calcium deposits accumulate within these granulomas, creating the characteristic hardened appearance visible on X-rays and CT scans. This calcification process typically indicates that the original inflammatory trigger has been successfully contained or eliminated.

Common causes of calcified granulomas include previous infections such as tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, or other fungal diseases. Exposure to certain environmental particles, autoimmune conditions, and even some medications can also trigger granuloma formation. In many cases, people develop these formations without ever experiencing noticeable symptoms from the original cause.

Key Differences Between Calcified and Non-Calcified Granulomas

The primary distinction between calcified and non-calcified granulomas lies in their stage of development and activity level. Non-calcified granulomas are typically newer formations that may still be actively responding to ongoing inflammation or infection.

Non-calcified granulomas appear as soft tissue masses on imaging studies and may continue to grow or change over time. They often require closer monitoring and sometimes active treatment, depending on the underlying cause and location.

In contrast, calcified granulomas are generally considered inactive or "healed" lesions. The presence of calcium deposits suggests that the inflammatory process has resolved, and these formations rarely grow or cause complications. However, they remain permanently visible on imaging studies as small, bright white spots.

Recognizing Symptoms and Clinical Presentations

Most calcified granulomas produce no symptoms and are discovered incidentally during imaging studies performed for other reasons. However, symptoms may occur depending on the granuloma's size, location, and the underlying condition that caused its formation.

Lung-related calcified granulomas, which are among the most common, typically cause no respiratory symptoms. In rare cases where granulomas are large or numerous, patients might experience persistent cough, chest discomfort, or mild shortness of breath.

Calcified granulomas in other organs may produce location-specific symptoms. For example, those in the liver are usually asymptomatic, while granulomas in lymph nodes might occasionally cause mild swelling or tenderness. Brain granulomas, though extremely rare, could potentially cause neurological symptoms.

It's important to note that symptoms are more likely related to active, non-calcified granulomas or the underlying condition that caused the granuloma formation rather than the calcified granuloma itself.

Diagnostic Approaches and Imaging Techniques

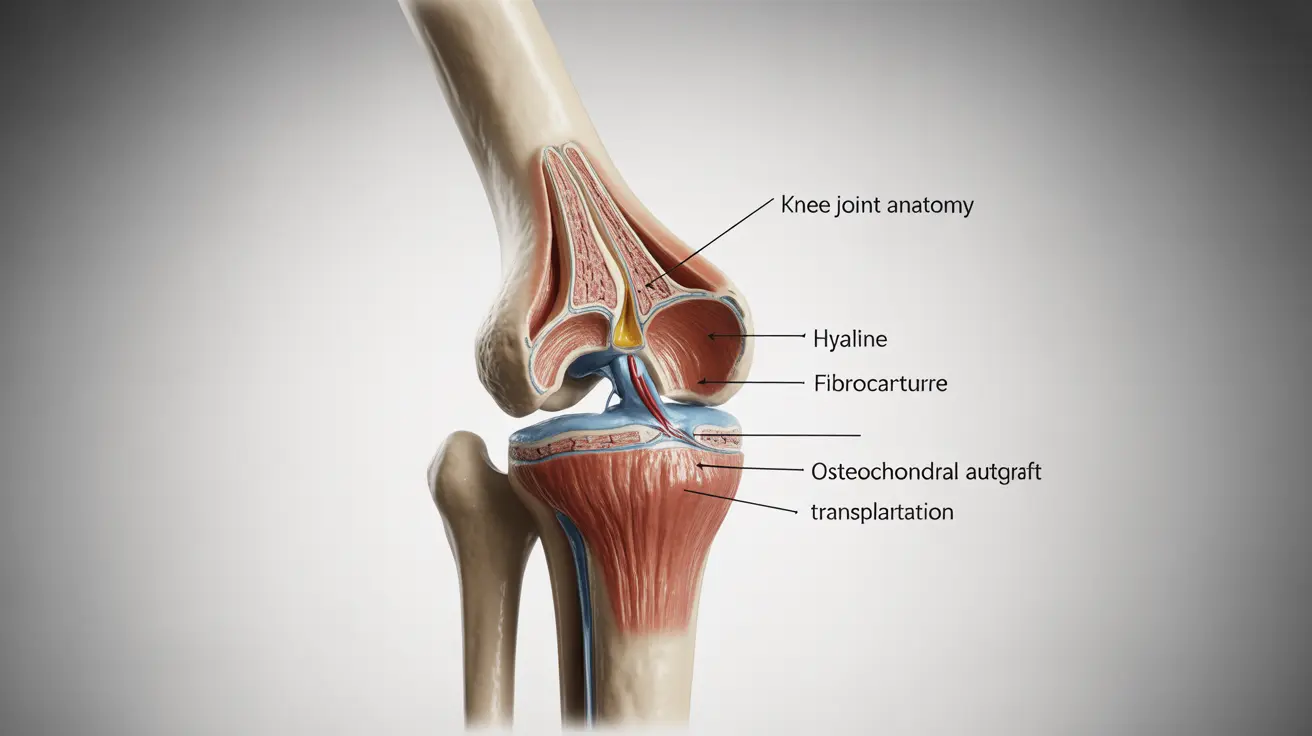

Calcified granulomas are most commonly detected through routine chest X-rays, where they appear as small, round, bright white spots. CT scans provide more detailed images and can better distinguish granulomas from other types of lung nodules or masses.

The key diagnostic challenge involves differentiating calcified granulomas from potentially malignant lesions. Radiologists look for specific characteristics including the pattern of calcification, size, shape, and location. Calcified granulomas typically display central or "popcorn-like" calcification patterns that are distinct from the irregular calcification sometimes seen in cancerous tumors.

When imaging results are unclear, additional tests may be necessary. These might include PET scans to assess metabolic activity, comparison with previous imaging studies to evaluate changes over time, or in rare cases, tissue biopsy to confirm the diagnosis definitively.

Blood tests may also be performed to check for signs of active infection or autoimmune conditions that could indicate ongoing granulomatous disease requiring treatment.

Treatment Considerations and Management Strategies

The vast majority of calcified granulomas require no active treatment since they represent resolved inflammatory processes. Medical management typically involves periodic monitoring through follow-up imaging to ensure the granulomas remain stable over time.

Treatment becomes necessary only when imaging or clinical evidence suggests active, ongoing granulomatous disease. In these cases, therapy targets the underlying cause rather than the calcified granulomas themselves.

For active infections causing granuloma formation, appropriate antimicrobial medications are prescribed. Fungal infections might require antifungal drugs, while bacterial infections are treated with specific antibiotics. Autoimmune-related granulomatous diseases may benefit from immunosuppressive medications or corticosteroids.

Surgical removal of calcified granulomas is rarely necessary and typically reserved for cases where the diagnosis remains uncertain despite extensive testing, or when granulomas cause mechanical problems due to their size or location.

Long-Term Outlook and Health Implications

Calcified granulomas carry an excellent long-term prognosis and rarely cause health complications. These formations are considered stable, inactive lesions that do not grow, spread, or interfere with organ function in the vast majority of cases.

The main clinical significance of calcified granulomas lies in their potential to create anxiety when discovered unexpectedly on imaging studies. Understanding their benign nature helps patients and healthcare providers make informed decisions about follow-up care.

Regular monitoring through periodic imaging may be recommended, particularly for newly discovered granulomas, but the frequency of follow-up typically decreases over time as stability is confirmed.

Frequently Asked Questions

What causes calcified granulomas and how are they different from non-calcified granulomas?

Calcified granulomas develop when the immune system forms protective barriers around persistent irritants, infections, or foreign substances. Over time, calcium deposits accumulate in these structures, creating the hardened appearance visible on medical imaging. Non-calcified granulomas are typically newer, potentially active formations that may still be responding to ongoing inflammation, while calcified granulomas represent healed, inactive lesions that have successfully contained the original trigger.

What symptoms might indicate a calcified granuloma is affecting my lungs or another organ?

Most calcified granulomas produce no symptoms and are discovered incidentally during imaging studies. When symptoms occur, they depend on location and size. Lung granulomas rarely cause respiratory symptoms, but large or numerous granulomas might occasionally cause persistent cough or mild chest discomfort. Granulomas in other organs typically remain asymptomatic, though those in lymph nodes might cause mild swelling.

How are calcified granulomas diagnosed and distinguished from cancer on imaging tests?

Calcified granulomas are diagnosed primarily through imaging studies like X-rays and CT scans, where they appear as small, bright white spots with characteristic calcification patterns. Radiologists distinguish them from cancer by examining the calcification pattern, size, shape, and location. Granulomas typically show central or "popcorn-like" calcification, while cancerous lesions may have irregular calcification patterns. Additional tests like PET scans or tissue biopsy may be needed when imaging results are unclear.

Do calcified granulomas require treatment, and what treatments are used if the underlying cause is active?

Calcified granulomas themselves rarely require treatment since they represent resolved inflammatory processes. Treatment is only necessary when there's evidence of active, ongoing granulomatous disease. In such cases, therapy targets the underlying cause with appropriate medications: antifungal drugs for fungal infections, antibiotics for bacterial infections, or immunosuppressive medications for autoimmune-related conditions. Most patients only need periodic monitoring through follow-up imaging.

Can a calcified granuloma become cancerous or cause long-term health problems?

Calcified granulomas do not become cancerous and rarely cause long-term health problems. These formations are considered stable, inactive lesions that typically do not grow, spread, or interfere with organ function. They carry an excellent long-term prognosis and represent evidence of the body's successful response to previous inflammatory challenges. The main clinical significance is ensuring proper diagnosis to distinguish them from other conditions that might require treatment.