Anemia, a condition where the body lacks sufficient healthy red blood cells to carry oxygen throughout the body, can arise from various causes - both genetic and non-genetic. Understanding the role of genetics in anemia is crucial for proper diagnosis, treatment, and management of this common blood disorder.

While some people inherit certain types of anemia through their genes, others may develop the condition due to dietary factors, medical conditions, or other environmental influences. Let's explore the complex relationship between genetics and anemia to better understand this important health condition.

Types of Inherited Anemia

Several forms of anemia have genetic components, passed down through families across generations. These inherited conditions affect how the body produces or maintains healthy red blood cells:

Sickle Cell Anemia

This inherited condition causes red blood cells to become crescent-shaped and rigid, leading to blocked blood flow and decreased oxygen delivery throughout the body. It's inherited when both parents carry the sickle cell trait.

Thalassemia

This genetic condition affects the body's ability to produce normal hemoglobin. There are different types of thalassemia, ranging from mild to severe, depending on the specific genetic mutations involved.

Hereditary Spherocytosis

This inherited condition causes red blood cells to become sphere-shaped and fragile, leading to their premature breakdown in the spleen.

Non-Genetic Causes of Anemia

Many cases of anemia develop from factors unrelated to genetics, including:

- Iron deficiency

- Vitamin B12 deficiency

- Chronic diseases

- Blood loss

- Certain medications

- Pregnancy

Diagnosis and Testing

Determining whether anemia has a genetic component involves several steps:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Family history assessment

- Genetic testing when appropriate

- Hemoglobin electrophoresis

- Bone marrow examination in some cases

Treatment Approaches

Treatment strategies vary significantly depending on whether the anemia is genetic or acquired:

Genetic Anemia Treatment

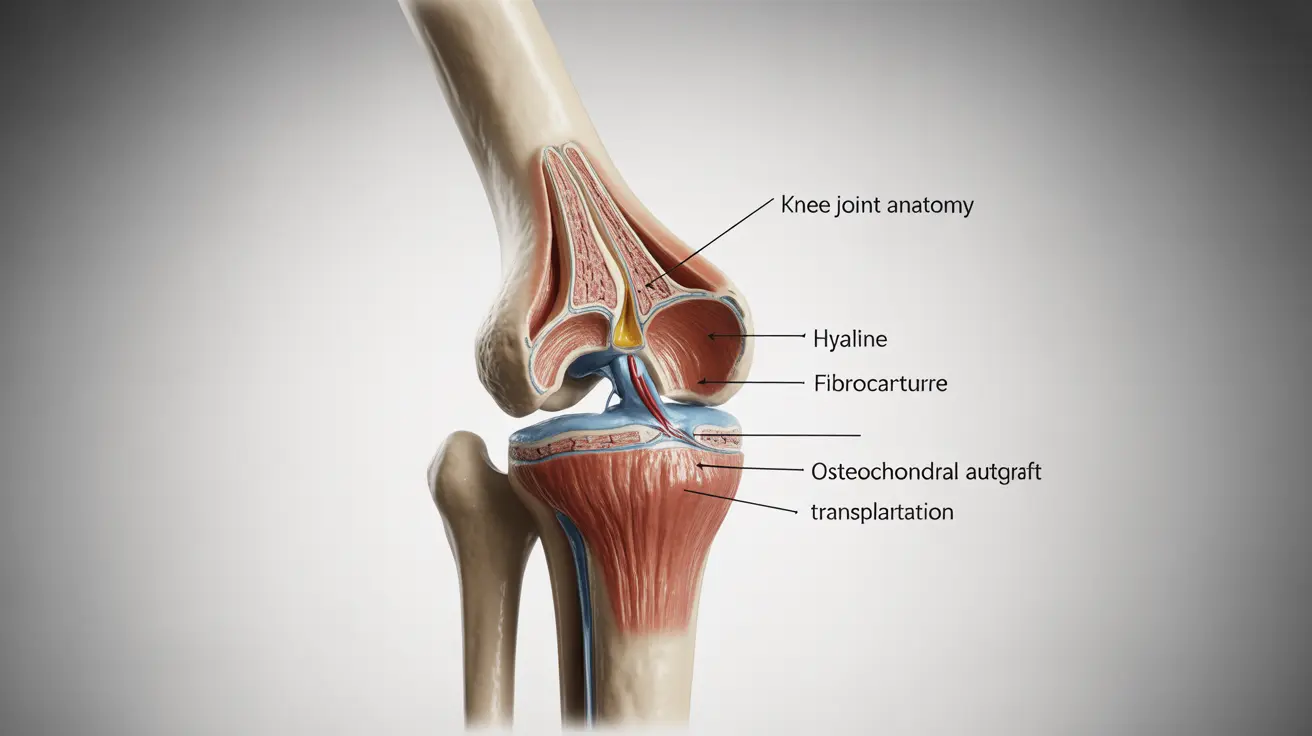

Management of genetic anemias often requires specialized approaches such as:

- Regular medical monitoring

- Blood transfusions

- Gene therapy (in some cases)

- Bone marrow transplantation

- Specialized medications

Non-Genetic Anemia Treatment

Treatment for non-genetic anemia typically focuses on addressing the underlying cause:

- Iron supplementation

- Dietary changes

- Vitamin B12 injections

- Treatment of underlying conditions

Frequently Asked Questions

- Is anemia always genetic or can it be caused by other factors?

No, anemia is not always genetic. While some forms are inherited, many cases of anemia are caused by nutritional deficiencies, chronic diseases, blood loss, or other environmental factors.

- What types of anemia are inherited and how are they passed down in families?

Common inherited anemias include sickle cell disease, thalassemia, and hereditary spherocytosis. These conditions are typically passed down through autosomal recessive or dominant inheritance patterns, meaning they require specific genetic contributions from parents.

- How can I find out if my anemia is caused by a genetic mutation?

Genetic testing, along with a thorough family history and specific blood tests like hemoglobin electrophoresis, can help determine if your anemia has a genetic cause. Your healthcare provider can recommend appropriate testing based on your symptoms and family history.

- What are the common symptoms of genetic anemias like sickle cell disease and thalassemia?

Common symptoms include fatigue, shortness of breath, pale skin, jaundice, delayed growth in children, and pain crises (particularly in sickle cell disease). The severity and specific symptoms can vary depending on the type of genetic anemia.

- Can genetic anemia be treated or managed differently from nutritional anemia?

Yes, genetic anemias typically require more complex and long-term management strategies compared to nutritional anemia. While nutritional anemia often improves with supplements and dietary changes, genetic anemias may require ongoing medical care, regular transfusions, or specialized treatments like gene therapy.