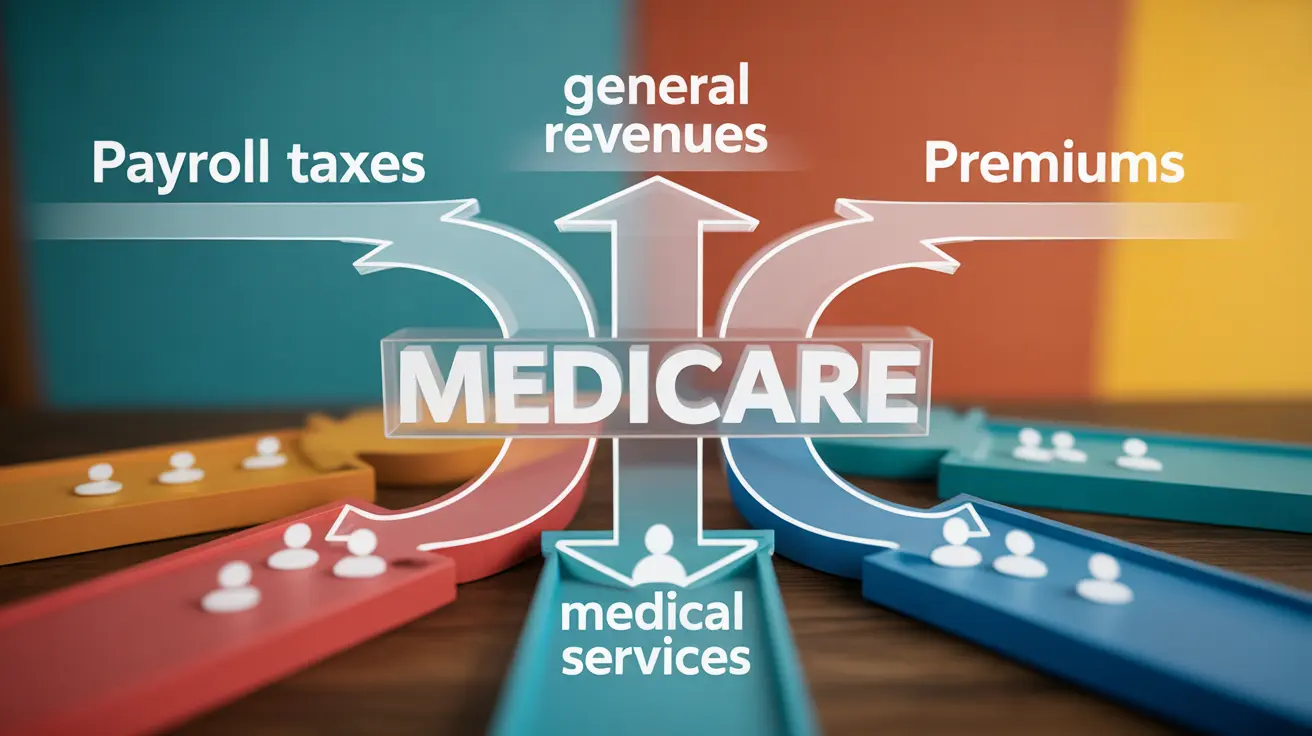

Medicare serves as a crucial healthcare safety net for millions of Americans aged 65 and older, as well as certain younger individuals with disabilities. Understanding how Medicare funds are collected is essential for both current beneficiaries and those planning for their healthcare future. The program's complex funding structure involves multiple revenue sources, from payroll taxes to premiums, each playing a vital role in maintaining this cornerstone of American healthcare.

The financial sustainability of Medicare has become increasingly important as the baby boomer generation continues to age and healthcare costs rise. By examining how Medicare collects its funding, we can better appreciate the intricate balance between taxpayer contributions, beneficiary payments, and government allocations that keep this essential program operational.

The Foundation of Medicare Funding: Payroll Tax Collection

The primary mechanism through which Medicare funds are collected centers on payroll taxes deducted from workers' paychecks. Every working American contributes to Medicare through the Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) tax, which specifically includes a Medicare component of 2.9% of earnings. This tax is split equally between employees and employers, with each party contributing 1.45% of the worker's wages.

High-income earners face an additional Medicare tax burden through the Additional Medicare Tax, implemented as part of the Affordable Care Act. Workers earning more than $200,000 annually (or $250,000 for married couples filing jointly) pay an extra 0.9% Medicare tax on income above these thresholds. Unlike the standard Medicare tax, this additional levy is paid entirely by the employee, with no employer matching contribution.

Self-employed individuals must cover both the employee and employer portions of Medicare taxes, resulting in a total Medicare tax rate of 2.9% on their net earnings from self-employment. This ensures that all working Americans contribute to Medicare funding regardless of their employment status.

Understanding Medicare Part A vs Part B Funding Mechanisms

Medicare's funding structure varies significantly between its different parts, with Part A and Part B relying on distinctly different revenue sources. Medicare Part A, which covers hospital insurance, operates primarily through the Medicare Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund. This trust fund receives its revenue almost exclusively from the payroll taxes mentioned above, making it largely self-funded through worker contributions.

Medicare Part B, covering outpatient medical services and physician visits, follows a different funding model. Part B operates through the Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) Trust Fund, which receives approximately 75% of its funding from general federal revenues and about 25% from beneficiary premiums. This funding structure means Part B relies more heavily on broader government funding rather than dedicated payroll taxes.

Part C (Medicare Advantage) and Part D (prescription drug coverage) also utilize the SMI Trust Fund structure, combining general revenues with beneficiary premiums. This diversified funding approach helps ensure program stability while distributing costs across multiple revenue streams.

Premium Obligations Despite Payroll Tax Contributions

Many Americans are surprised to learn that paying Medicare payroll taxes throughout their working years doesn't eliminate all Medicare-related costs during retirement. While Part A coverage is typically premium-free for individuals who have paid Medicare taxes for at least 40 quarters (10 years), beneficiaries must still pay monthly premiums for most other Medicare services.

Medicare Part B requires monthly premium payments from nearly all beneficiaries, regardless of their previous payroll tax contributions. These premiums are income-adjusted, meaning higher-income beneficiaries pay more through the Income-Related Monthly Adjustment Amount (IRMAA). The standard Part B premium serves as a crucial funding source for outpatient medical services.

Additional Medicare coverage options, such as Part D prescription drug plans and Medigap supplemental insurance, also require separate premium payments. These costs reflect the reality that payroll taxes alone cannot fully fund the comprehensive healthcare coverage that Medicare provides to its beneficiaries.

Current Medicare Costs for Beneficiaries in 2024 and 2025

Medicare costs for beneficiaries have experienced notable changes between 2024 and 2025. In 2024, the standard Medicare Part B premium was $174.70 per month, with an annual deductible of $240. Higher-income beneficiaries faced additional charges through IRMAA, with surcharges ranging from $69.90 to $419.30 per month depending on income levels.

For 2025, Medicare costs have seen adjustments reflecting healthcare inflation and program expenses. The standard Part B premium increased to $185 per month, while the annual deductible rose to $257. These increases, though modest compared to private insurance rate changes, still represent additional financial obligations for Medicare beneficiaries.

Part A costs, while premium-free for most beneficiaries, include deductibles and coinsurance requirements. In 2025, the Part A deductible for hospital stays is $1,676 per benefit period, with additional daily coinsurance charges for extended stays. These out-of-pocket costs highlight the importance of understanding Medicare's cost-sharing structure.

Medicare's Financial Future and Trust Fund Sustainability

The long-term sustainability of Medicare funding has become a pressing concern as demographic changes strain the program's finances. The Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, which supports Part A benefits, faces projected depletion in the early 2030s based on current contribution and spending trends. This timeline reflects the challenge of maintaining adequate funding as the ratio of workers to beneficiaries continues to decline.

If Medicare trust funds were to become depleted, the program wouldn't disappear entirely, but benefits would face automatic reductions. Current projections suggest that Part A could only pay approximately 90% of scheduled benefits if trust fund reserves are exhausted. Such reductions would significantly impact beneficiaries' access to hospital and skilled nursing services.

Policymakers continue to explore various solutions to address Medicare's funding challenges, including potential changes to payroll tax rates, benefit structures, and eligibility requirements. These discussions underscore the importance of understanding how Medicare funds are collected and the ongoing need for sustainable financing mechanisms.

Frequently Asked Questions

How are Medicare funds collected and what types of taxes pay for it?

Medicare funds are collected primarily through payroll taxes, with employees and employers each contributing 1.45% of wages (2.9% total). High earners pay an additional 0.9% on income above $200,000 ($250,000 for couples). General federal revenues and beneficiary premiums also contribute to Medicare funding, particularly for Parts B and D.

What is the difference between Medicare Part A and Part B funding sources?

Medicare Part A is funded almost entirely through payroll taxes collected in the Hospital Insurance Trust Fund. Part B relies on a combination of general federal revenues (approximately 75%) and beneficiary premiums (about 25%) through the Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Fund. This makes Part A more dependent on worker contributions while Part B draws from broader government funding.

Do I have to pay premiums for Medicare if I'm already paying payroll taxes?

Yes, payroll taxes primarily cover Medicare Part A benefits, which are typically premium-free for qualified beneficiaries. However, you must still pay monthly premiums for Part B (outpatient services), Part D (prescription drugs), and any Part C (Medicare Advantage) plans you choose. Payroll taxes alone don't eliminate all Medicare-related costs during retirement.

How much does Medicare cost per month for beneficiaries in 2024 and 2025?

In 2024, the standard Part B premium was $174.70 monthly with a $240 deductible. For 2025, the Part B premium increased to $185 monthly with a $257 deductible. Higher-income beneficiaries pay additional IRMAA surcharges. Part A has no premium for most beneficiaries but includes a $1,676 deductible per benefit period in 2025.

Will Medicare run out of money and what happens if the trust funds are depleted?

The Medicare Hospital Insurance Trust Fund faces projected depletion in the early 2030s. If depleted, Medicare wouldn't disappear, but Part A benefits would be automatically reduced to match incoming revenue, potentially paying only about 90% of scheduled benefits. Congress would need to act to restore full funding through tax increases, benefit changes, or other financing mechanisms.