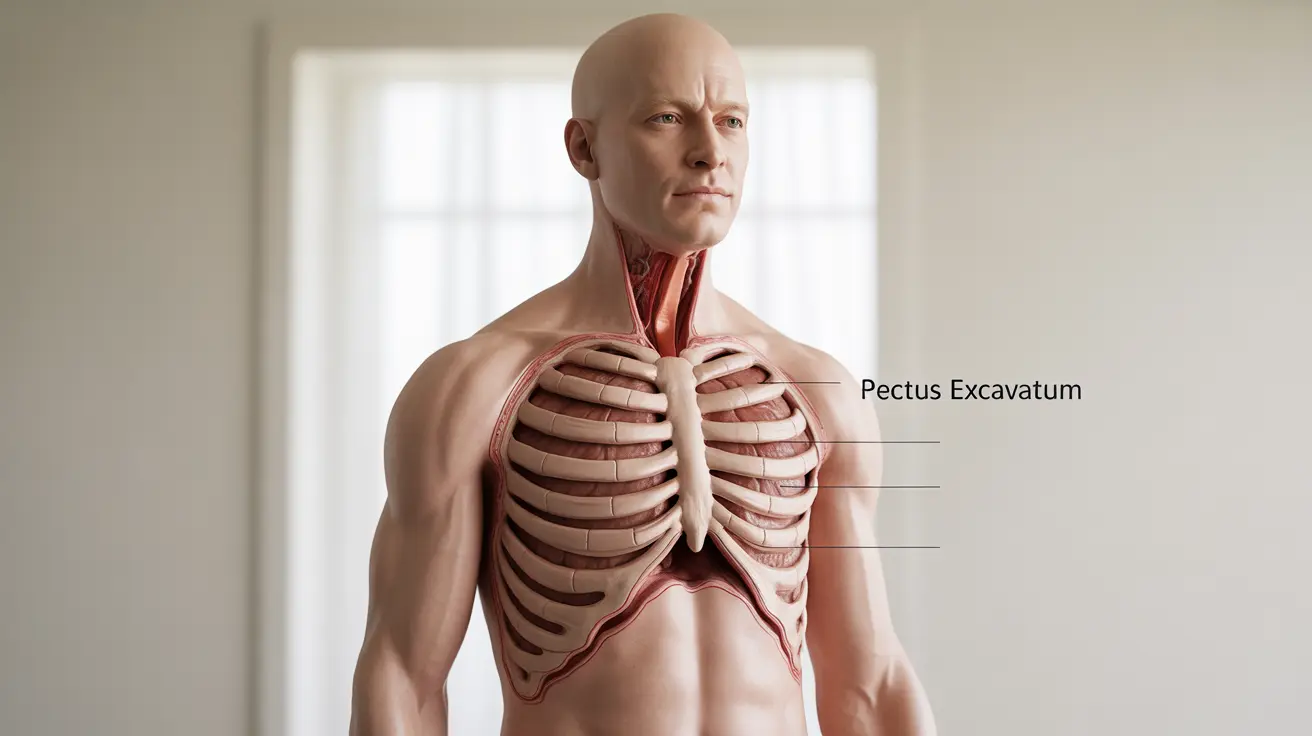

Pectus excavatum, commonly known as "funnel chest," is a chest wall deformity that affects approximately 1 in 400 births, making it the most common congenital chest wall abnormality. This condition occurs when the breastbone (sternum) and surrounding rib cartilage grow inward, creating a sunken or caved-in appearance in the center of the chest.

Understanding the underlying pectus excavatum causes is crucial for families dealing with this condition, as it helps inform treatment decisions and provides insight into what to expect for future generations. While the physical appearance may be the most noticeable aspect, the causes behind this condition involve complex genetic and developmental factors that medical professionals continue to study.

What Triggers Pectus Excavatum Development

The primary pectus excavatum causes stem from abnormal growth patterns of the cartilage that connects the ribs to the breastbone. During fetal development and throughout childhood growth periods, this costal cartilage may grow excessively or unevenly, pushing the sternum inward and creating the characteristic sunken chest appearance.

Medical researchers have identified that the condition typically develops during periods of rapid growth, particularly during infancy and adolescence. The excessive growth of the lower costal cartilages creates an imbalance that forces the sternum to curve inward, rather than maintaining its normal outward projection.

Environmental factors during pregnancy, such as intrauterine positioning or pressure, may also contribute to the development of pectus excavatum, though these influences are less well understood than the genetic components.

Genetic Factors and Family History

Strong evidence supports hereditary factors as significant pectus excavatum causes. Studies indicate that approximately 25-40% of individuals with pectus excavatum have at least one family member with the same condition or another chest wall deformity.

The inheritance pattern appears to be autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance, meaning that while the genetic predisposition can be passed from parent to child, not everyone who inherits the genes will develop the visible condition. This explains why some families may have multiple affected members across generations, while others may see the condition skip generations entirely.

Genetic research has identified several chromosomal regions that may be associated with pectus excavatum development, though scientists have not yet isolated specific genes responsible for the condition. This ongoing research continues to provide valuable insights into the hereditary nature of this chest wall deformity.

Associated Medical Conditions

Pectus excavatum frequently occurs alongside other genetic conditions, which provides additional clues about its underlying causes. Marfan syndrome, a connective tissue disorder, is associated with pectus excavatum in approximately 50% of cases. Similarly, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and other connective tissue disorders show increased rates of chest wall deformities.

Scoliosis, or curvature of the spine, occurs more frequently in individuals with pectus excavatum than in the general population. This association suggests that common developmental or genetic factors may affect multiple aspects of skeletal growth and formation.

These connections between pectus excavatum and other conditions help medical professionals understand the broader genetic and developmental factors that contribute to chest wall deformities.

Impact on Respiratory and Cardiac Function

While the cosmetic appearance often receives the most attention, understanding how pectus excavatum causes functional problems is equally important. The inward curvature of the chest wall can compress the lungs and heart, potentially affecting their normal function.

Respiratory symptoms may include shortness of breath during exercise, reduced lung capacity, and difficulty with deep breathing. These symptoms often become more pronounced during adolescence when the chest wall deformity may worsen with growth spurts.

Cardiac effects can include heart palpitations, chest pain, and in severe cases, compression of the heart that affects its ability to fill properly with blood. These functional impacts often play a crucial role in determining whether treatment is necessary.

Signs and Symptoms to Monitor

Recognizing the symptoms of pectus excavatum helps families understand when medical evaluation may be beneficial. The most obvious sign is the visible sunken appearance of the chest, which may be present at birth or develop gradually during childhood.

Physical symptoms can include fatigue during physical activities, frequent respiratory infections, chest pain, and heart palpitations. Some individuals may experience psychological impacts related to body image concerns, particularly during adolescence when self-consciousness about appearance often peaks.

Many people with mild pectus excavatum experience no symptoms at all and lead completely normal lives without requiring any treatment. However, monitoring for functional symptoms helps determine if medical intervention might be beneficial.

Treatment Approaches and Timing

Treatment options for pectus excavatum range from non-surgical approaches to surgical correction, depending on the severity of the condition and associated symptoms. Non-surgical methods include physical therapy exercises designed to strengthen chest muscles and improve posture, as well as vacuum bell therapy, which uses suction to gradually pull the chest wall outward.

Surgical intervention, typically the Nuss procedure or Ravitch technique, is usually reserved for cases where the condition causes significant functional problems or severe psychological distress. The optimal timing for surgery is often during adolescence when the chest wall is still flexible but growth is nearly complete.

The decision to pursue treatment depends on multiple factors, including the severity of the deformity, presence of symptoms, psychological impact, and patient preferences. Working with experienced medical professionals helps families make informed decisions about the most appropriate approach.

Frequently Asked Questions

What causes pectus excavatum and is it inherited?

Pectus excavatum is caused by abnormal growth of the cartilage connecting the ribs to the breastbone, which pushes the sternum inward. The condition has a strong hereditary component, with 25-40% of affected individuals having family members with similar chest wall deformities. It follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern with incomplete penetrance, meaning genetic predisposition can be passed down but doesn't always result in visible symptoms.

How can pectus excavatum affect breathing and heart function?

Pectus excavatum can compress the lungs and heart due to the inward curvature of the chest wall. This compression may cause shortness of breath during exercise, reduced lung capacity, difficulty with deep breathing, heart palpitations, and chest pain. In severe cases, cardiac compression can affect the heart's ability to fill properly with blood, though many people with mild forms experience no functional problems.

What are the common symptoms of pectus excavatum to watch for?

Common symptoms include the visible sunken chest appearance, fatigue during physical activities, frequent respiratory infections, chest pain, heart palpitations, and shortness of breath during exercise. Some individuals may also experience psychological effects related to body image concerns. However, many people with mild pectus excavatum have no symptoms and require no treatment.

What treatment options are available for pectus excavatum, and when is surgery recommended?

Treatment options include non-surgical approaches like physical therapy exercises and vacuum bell therapy, as well as surgical procedures such as the Nuss procedure or Ravitch technique. Surgery is typically recommended when the condition causes significant functional problems, severe psychological distress, or measurable cardiac or pulmonary compression. The decision depends on symptom severity, psychological impact, and individual patient factors.

Can non-surgical therapies like physical therapy or vacuum bell help improve pectus excavatum?

Yes, non-surgical therapies can be beneficial for some individuals with pectus excavatum. Physical therapy exercises focus on strengthening chest muscles and improving posture, which can help minimize the appearance and functional impact. Vacuum bell therapy uses suction to gradually pull the chest wall outward and has shown promising results, particularly in younger patients with flexible chest walls. These approaches work best for mild to moderate cases and are often tried before considering surgical options.